| 24.09. 2011 – 07.12. 2011 | Public Folklore (co-production steirischer herbst 2011) |

|

Fotocredit: Johanna Glösl, Courtesy Grazer Kunstverein

Public Folklore

Eröffnung | Opening 24. September 2011 um 17:00 Uhr | September 24 at 5 pm

Mit | with

STEIRISCHER HERBST

PUBLIC FOLKORE (scroll down for english version)

In den meisten Ländern Europas beobachten wir eine zunehmende Tendenz der nationalistischen Selbstkonstruktion in Kultur und Politik.

Ungarn: Jobbik Partei Anhänger (die paramilitärische Magyar Gárda / Ungarische Garde), 2010, ein Beispiel dafür, wie eine nationalistische Politik ihren eigenen Folklorismus produziert - in Form einer eigenen Tracht. Die Analyse der einzelnen Elemente der Tracht zeigt, dass diese völlig divergente kulturelle Einflüsse adaptiert.

Das Projekt geht von der Annahme aus, dass gegenwärtige Erscheinungsformen des Folklorismus nicht nur als ein Instrument nationalistischer Politik zu verstehen sind sondern darüber hinaus auch als deren eigentliche Produktion. Denn nationalistische Politik resultiert dort, wo sie erfolgreich ist, in der Folklorisierung des Öffentlichen... einer inszenierten und künstlich hergestellten homogenen Realität.

Die künstlerischen Produktionen in Public Folklore setzen sich kritisch mit aktuellen Phänomenen der Folklorisierung in Politik, Medien, Tourismus, Populärkultur und Kommerz auseinander. Was bedeutet die Ausübung des Folklorismus für die Lebenswelt der Menschen? Was sind die Auswirkungen auf die Alltagskultur? Und welche Intentionen stecken dahinter? Dabei analysieren einige die politischen Zusammenhänge und gesellschaftlichen Auswirkungen, während andere durch konkrete Aktionen Gegenrealität herstellen oder in der Projektarbeit bsp. eine als folkloristisch adaptierte Tradition von ihrer Stilisierung befreien.

Zugleich arbeitet Public Folklore mit wissenschaftlichen Ansätzen aus den Bereichen Ethnologie, Visuelle Anthropologie und Soziologie zusammen.

Folklore, Nationalismus und Politik:

The finnish maiden, National Board of Antiquities

Der Zusammenhang zwischen Folklore und Nationalismus besteht bereits seit deren Anfängen.

Julia Timoschenko und Timoschenko-Poster in Wohnung (unter Ikone)

Eine der Parteien, die für Kataloniens Eigenständigkeit kämpft: Die linksnationalistischen Separatisten der ERC

Durch die (nationalstaatlichen) Transformationen im Europa des 19. Jhd. gab es ein vermehrtes Interesse an den identitätsstiftenden Erzählungen von der gemeinsamen Volkskultur. Viele solcher Erzählungen bzw. ihre adaptierten Kopien gewinnen heute zunehmend an Popularität zurück. Sie werden gebraucht, um aktuelle Politik zu legitimieren. Aus ihnen werden u.a. territoriale Ansprüche abgeleitet, die Ausgrenzung anderer Ethnien und Sprachen legitimiert oder Leitkulturen aufgestellt.

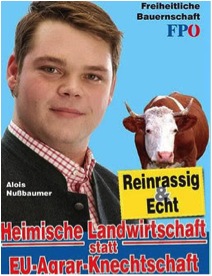

FPÖ, Österreich, 2010

Insofern betrachtet das Projekt den Folklorismus als eine doppelte Konstruktion:

Aufsteirern, Graz, 2009

Die Entdeckung der Folklore basiert außerdem von Beginn an auf einer um die Wende vom 18. zum 19. Jahrhundert einsetzenden Romantisierung der Landschaft und ihrer BewohnerInnen durch das Bürgertum.

“Russian dress and traditional symbols are a part of Russian culture. This girl, in traditional Russian clothing, is presenting a loaf of bread symbolizing welcome or hospitality. In the traditional "bread and salt" ceremony, a cellar of salt was placed upon the loaf of bread (usually presented upon an embroidered towel) during celebrations of welcome and marriage. This tradition is still sometimes practiced. The traditional dress worn by this girl is called as sarafan and the traditional cap is called a kokoshnik.” (http://goeasteurope.about.com/od/easterneuropedestinations/tp/easterneuropeculturephotos.htm)

Prozesse der Folklorisierung lassen sich in allen europäischen Ländern finden. Dabei gibt es partiell unterschiedliche Ursachen und historische Kontexte für ihr Erscheinen. Und Folklorismus ist (wie oben dargestellt) auch kein neues Phänomen. Aber: In seiner konkret politischen Nutzung und Spielform hat der aktuelle Folklorismus eine starke Renaissance erlebt.

Baskischer Fischertanz

Soziokulturelle Zusammenhänge/Hintergründe:

Kurator

Veranstaltungen | Events

"Wie das Eigene zum Fremden und wieder zum Eigenen wurde: Folklore im Stadtraum Graz"

Stadtrundgang mit Angela Praßl Termine: 8.10.2011, 15.10.2011 & 5.11.2011, jeweils 11:00-13:30 Uhr Treffpunkt: Vorplatz Volkskundemuseum Die Teilnahme ist kostenlos. Um Anmeldung wird gebeten.

„Ach das Nationale ist immer so schön!“ Im modernen Europa haben Nation und Nationalstaat scheinbar an Legitimität verloren. Doch sind die kollektiven Mentalitäten nach wie vor zutiefst davon geprägt, v.a. im postkommunistischen Osten. Noch stärker gilt dies für die außereuropäischen Regional- und Großmächte im Zeitalter der Globalisierung. Der Vortrag soll die Widerspiegelung des Nationalgedankens in z.T. weniger bekannten künstlerischen Zeugnissen des 19. Jhs. und seine fortwährende Prägekraft anhand ausgewählter historischer Stationen beleuchten. Schwerpunkt ist naturgemäß Frankreich als historisches Exempel für die moderne Nationsbildung als kollektiver Willensakt schlechthin.

KIZ RoyalKino & Grazer Kunstverein proudly announce:

"Public Folklore"

Kurzfilme und -videos von KünstlerInnen präsentiert Søren Grammel am Dienstag, 22.11.2011 um 18:00 Uhr

Ort: KIZ RoyalKino, Conrad-von-Hötzendorfstraße 10

Gesamtspielzeit: 53‘52“ Im Rahmen der Austellung „Public Folklore“ präsentiert der Grazer Kunstverein in Zusammenarbeit mit dem KIZ RoyalKino einen themenbezogenen Kurzfilmabend. Die künstlerischen Produktionen in „Public Folklore“ setzen sich mit aktuellen Phänomenen der Folklorisierung in Politik und Populärkultur auseinander. Dabei analysieren sie in unterschiedlicher Weise die politischen Zusammenhänge — insbesondere in postsozialistischen Gesellschaften — die dem Phänomen folkloristisch adaptierter Tradition seinen Raum geben. Programm: Jesper Nordahl, Crazy Girls, 2001, DVD, 8’25’’ Eva Mag, A Papir Székely, 2011, DVD, 21’17’’ Mari Laanemets & Killu Sukmit, The Cure, 1999, DVD, 6‘30” Almut Rink, Past Perfect, 2003, DVD, 27’40’’

"Die Parade"

Ein Projekt von Annika Eriksson Termin: 24.09.2011, 17:30 Uhr Treffpunkt: Grazer Kunstverein

Fotocredit: Stefan Postl, Courtesy Grazer Kunstverein Siehe auch folgende Besprechung auf www.gat.st: http://www.gat.st/pages/de/nachrichten/5066.htm

(english)

Public Folklore "Cultural heritage is not the same thing as national identity." (Anthony C. Grayling)

We face a constantly increasing tendency to national self-construction in culture and politics in almost every country in Europe for several years. In conjunction with these events, the project queries the function of folklorism within the formation of political belief- and valuesystems.

Jobbik party members (the paramilitary Magyar Gárda / = Hungarian Guard), 2010, an example of how nationalist politics produces its own folklorism – in the form of its own costume. The analysis of individual elements of the costume show that they have been adapted and constructed from completely divergent cultural influences.

The point of departure for the project is that current manifestations of folklorism are not only to be understood as an instrument of nationalist politics, but also as their actual production as well. For nationalist politics results, where it is successful, in folklorizing the public sphere... a staged and artificially produced homogeneous reality.

Artistic productions in Public Folklore will critically explore current phenomena of folklorization in politics, media, tourism, popular culture and commercialism. What does the exercise of folkorism mean for people’s world of life? What are its effects on everyday culture? And which intentions are behind it? Some analyze the political contexts and social impacts, whereas others produce counter-reality with concrete actions or in project work, for example by liberating a folkloristically adapted tradition from its stylization.

The exhibition is based on the observation (and current academic research findings) that folklore and folklorist signs are consciously (re-) employed and instrumentalized (not only) in Europe to create possibilities for nationalist identification and to thus produce communities and majorities (as well as minorities and marginalization on the other end).

The Finnish maiden, National Board of Antiquities: “... one could believe: when one speaks explicitly about nationality, that one is speaking of a timeless order that is greater than profane, gendered life. Nationality is something sublime and immaterial. Behind these immaterial ideas, however, gendered bodies appear. Behind the genderless »nostrischen» [fi. meinen ← me ‘we’] facades of society, mothers and fathers, daughters and sons become visible, all in their own places. The woman is the »care-giver», the mother of society and of the nation, and wherever she goes, she – unlike the man – is followed by home and family as context. Symptomatic for this »flat» gender order is that the position of the woman is always compared with that of the man, never the other way around. The stable identifiability is repeated in texts, even if the paradigms, methods and so-called academic trends change. The seemingly stable gender order becomes a unified, inseparable opinion system that is common to »all». Here I will call this order national gender. [Kirsti Lempiäinen in Gordon & al. 2002: 33]“

The connection between folklorism and nationalism has already existed since the beginning.

Julia Tymoshenko and Tymoshenko poster in an apartment (under icon)

One of the parties fighting for Catalonia’s independence: the leftist-nationalist separatists of the ERC

The (nation-state) transformations in Europe of the 19th century resulted in an increased interest in the narratives of common folk culture on which identity was founded.

FPÖ, Austria, 2010

Following from this, the project considers folklorism as a double construction:

Aufsteirern, Graz, 2009

Moldavia at the Eurovision song contest in Moscow

In addition, from the beginning the discovery of folklore has been based on a bourgeois romanticization of landscape and its inhabitants that began at the turn from the 18th to the 19th century.

“Russian dress and traditional symbols are a part of Russian culture. This girl, in traditional Russian clothing, is presenting a loaf of bread symbolizing welcome or hospitality. In the traditional "bread and salt" ceremony, a cellar of salt was placed upon the loaf of bread (usually presented upon an embroidered towel) during celebrations of welcome and marriage. This tradition is still sometimes practiced. The traditional dress worn by this girl is called as sarafan and the traditional cap is called a kokoshnik.” (http://goeasteurope.about.com/od/easterneuropedestinations/tp/easterneuropeculturephotos.htm)

Processes of folklorizing can be found in all European countries.

Basque Fisher Dance

Socio-Cultural Contexts/Backgrounds:

curator

|