|

Spring at Grazer Kunstverein

8 March – 24 May 2019

For Spring 2019 Grazer Kunstverein presented two new exhibitions by Sylvia Schedelbauer, the Berlin-based experimental filmmaker, and by Triple Candie, the Washington DC-based duo of art historians.

These separate and distinct exhibitions overlapped spatially, with Triple Candie’s discrete architectural interventions visibly occupying the entire building when the lights were on, from 11am – 2:30pm, and Sylvia Schedelbauer’s large-scale immersive video projections filling the galleries when the lights were off, from 2:30pm to 6pm daily.

Sylvia Schedelbauer

Collected Works 2004–2018

Sylvia Schedelbauer, Wishing Well, 2018, shown as part of Collected Works 2004–2018, Grazer Kunstverein, Spring 2019. Photography by kunst-dokumentation.com

Sylvia Schedelbauer produces experimental moving image works, that range from auto-biographical documentaries to visceral explorations of imagined scenarios. This exhibition is a large-scale immersive passage through Schedelbauer’s entire oeuvre, bringing us from her most recent work Wishing Well, 2018 right back to her first work Memories, 2004.

Installation view of Spring 2019 at Grazer Kunstverein. Photography by kunst-dokumentation.com

Over the years Schedelbauer has developed her own unique cinematic structural language to interrogate themes such as cultural dislocation, what it means to be transnational, the slippery shifts between fiction and reality, and memory, as an unreliable but compelling insight into history. She uses narrative tools like dream logic, biography, allegorical collage, free association and storytelling to create highly engaging sensory experiences, that sometimes take years to complete. Her flickering filmic works stretch and accelerate the potential of found footage. Often working with source material such as orphan films – educational, industrial, amateur footage, home movies and newsreels – from archives or personal collections, Schedelbauer manipulates imagery to transform it into something totally new. In this way she inhabits existing material, bending it to her will to form an original narrative of her own (re)construction, creating new versions of a story every time.

Sylvia Schedelbauer, Sea of Vapors, 2014, shown as part of Collected Works 2004–2018, Grazer Kunstverein, Spring 2019. Photography by kunst-dokumentation.com

Schedelbauer’s work is regularly screened at film festivals internationally. This exhibition marks her first solo show in a gallery context, and the first comprehensive exhibition of her complete works.

Sylvia Schedelbauer, way fare, 2009, shown as part of Collected Works 2004–2018, Grazer Kunstverein, Spring 2019. Photography by kunst-dokumentation.com

Sylvia Schedelbauer was born in Tokyo, and moved to Berlin in 1993 where she has been based since. She studied at the University of Arts Berlin (with Katharina Sieverding). Her films negotiate the space between broader historical narratives and personal, psychological realms mainly through poetic manipulations of found and archival footage. Selected screenings include Berlinale, Toronto International Film Festival, International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, London Film Festival, New York Film Festival, Robert Flaherty International Film Seminar and Stan Brakhage Symposium. Awards include the VG Bild-Kunst Award, the German Film Critics’ Award and the Gus Van Sant Award for Best Experimental Film.

Sylvia Schedelbauer, Wishing Well, 2018, shown as part of Collected Works 2004–2018, Grazer Kunstverein, Spring 2019. Photography by kunst-dokumentation.com

nownownow –

On the works of Sylvia Schedelbauer

Text by Alice Butler

For the most part, cinema goes to great lengths to conceal or distract from its piecemeal assembly. The labour invested in the fractured production of a single frame is often obscured by the polished outcome of the flat image. Fragmentation is an inexorable component of the medium however, not always something to overcome but arguably one of its great attributes, offering the possibility for infinite reconfiguration. This feature affords the filmmaker the unique albeit daunting opportunity to create something that closely resembles the elusive qualities of a thought process, with all the mysterious pathways, preoccupations and associations that this entails. It also allows for a more archaeological approach, one in which standard sequences give way to transparent images that peel back one by one to reveal what’s ‘around, or behind a picture’ rather than what comes next.1

Sylvia Schedelbauer’s films are composed predominantly of pre-existing footage, material that she draws from educational, industrial and amateur collections that includes home movies, travelogues and newsreels. The un-captioned segments, although extensive, are characterized by what art historian Charles Merewether describes as the ‘countermonumental’ – no landmarks, iconic events or familiar historical figures appear.2 In Sounding Glass (2011) for example we see snapshots of a forest, a murmuration, explosions on a battlefield, a Japanese woman carrying a baby on her back, sun bursting through the clouds. In their original contexts, these shots were cut-aways, fillers, accidents even, expressions of what is typically overlooked but presented together here, they amass as a portrait of a splintered collective psyche. Sounding Glass features a protagonist though, a man who stares intently into the lens of the camera at the film’s outset and about whom all the film’s questions of cultural dislocation caused by global conflict relate.

The forthright protagonist in Sounding Glass is somewhat of an anomaly in Schedelbauer’s filmography – elsewhere figures mostly shield their faces from view, unusually wary of being captured by the camera. They are solitary and nomadic, conveying a painful sense of alterity reminiscent of the peripatetic characters that populate the books of German writer W.G. Sebald, perhaps most notably in ‘Austerlitz’ (2001), a novel whose eponymous Jewish hero is born in the advent of the Second World War and sent as part of the Kindertransport to London. Adopted and raised by Welsh parents, who conceal his identity from him, Jacques Austerlitz subsequently becomes intent on uncovering his past. The conspicuous feeling of rootlessness evoked in Schedelbauer’s way fare (2009) resonates with the novel but so too does the story that emerges in Memories (2004), the artist’s first film in which she uses a collection of her German father’s photographs to try and unearth the closely guarded secrets of both his and her Japanese mother’s early lives in the immediate aftermath of World War II.

Memories and Schedelbauer’s second film Remote Intimacy (2007) are her only works in which voice-over features. From there, her focus is on developing an intensely visual language free from the confines of verbal speech. Soon the black insert appears, most obviously in False Friends (2007) giving expression perhaps to previously described gaps in family memory. Initially these dark single frames appear fairly evenly, creating more of a blinking rhythm than they do a sense of disturbance. In the opening section of Sounding Glass however, the black frames introduce the ‘frenzied inertia’ that critical theorist Francis Summers describes in relation to Austrian experimental filmmaker Martin Arnold’s Pièce touchée (1989), a 16 minute film that stretches out an 18 second extract from a 1950s American B-Movie that he says ‘mires the audience in a perpetual present that evokes a “now-now-now”’, a sensation of desired apprehension not dissimilar to the experience of absorbing some of Schedelbauer’s most recent works.3

Introducing a heightened sense of the present is an uncanny facet of Schedelbauer’s manipulation of mid-century footage. This masterful act of simultaneity – experiences of present and past co-existing within the same frame – does not only apply here. It is a structural device and conceptual framework fundamental to Schedelbauer’s three most recent films. Each of these works are marked by the evocation of divergent tempos for example; the slow pan that occurs in the close-up shot of a human eye in Sea of Vapors (2014) is offset by the speed of the flickering image of a forested landscape which is braided through it. This strategy captures the liminal and subliminal features of memory, making as much reference to the unfathomable process of forgetting as it does to the nature of recall. It also creates a powerful vortex for the viewer who is drawn in as the images seem to radiate out from the screen to inhabit the full space of the rooms they occupy. This somatic experience is the mark of any encounter with these films and the all-consuming force of their syncopated luminosity.

Schedelbauer tells of how she adopts the flicker in some cases as a means of facilitating what she would like to do with footage that she finds in a compromised state. The flicker enables her to extend out the duration of a scene for example – it means she can impose her will over the material rather than the other way around. Schedelbauer says however that she is also driven to find ways of making this so-called found material ‘speak more’, a phrase that reveals a desire to uncover hidden or latent significance in largely discarded footage. This connects strongly to the idea that images which are no longer, or in fact were never, in the public consciousness have particular worth because of what Bruce Conner describes as, ‘a philosophical premise that’s been around for a long time: if you want to know what’s going on in a culture look at the things that everybody takes for granted, and put a lot of emphasis on that rather than what they want to show you.’4

It is the act of combining as much as it is the act of selection that distinguishes Schedelbauer’s work with found footage though – hybridity is an essential component of what she does, blending two or more pieces of film to create a third, a fourth etc. This spawning of new material is a process of transformation that takes place on screen, each film living out a perpetual becoming, each precipice replacing the last. These shots exaggerate the ‘evanescence’ of the film image, the quality that places us as viewers under the command of the filmmaker who ultimately decides how long we see each shot and what it will be replaced by.5 This is a position that Schedelbauer assumes with unparalleled care, time and consideration, ensuring at every turn that the fragments she has unearthed for us always merit a second, much closer look.

1 Lucy Raven in conversation with Victoria Brooks in relation to her film The Deccan Trap (2015) refers to what she calls ‘a continuity of desire... to see around, or behind a picture’, http://www.vdrome.org/lucy-raven

2 Merewether, Charles, Introduction to Merewether, Charles (ed.), The Archive: Documents of Contemporary Art, Whitechapel, London and the MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachussets, 2006, p. 16.

3 Summers, Francis, (Re)Counting Love: Martin Arnold’s Pièce touchée (2011) https://extra.shu.ac.uk/transmission/papers/SUMMERS%20Francis.pdf

4 Conner, Bruce, quoted in Zyrd, Michael, ‘Found Footage Film as Discursive Metahistory: Craig Baldwin’s Tribulation 99’ in The Moving Image, University of Minnesota Press, Vol 2, No. 2, 2003, p. 40

5 Chion, Michel, Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen, Translated and Edited by Claudia Gorbman, Columbia University Press, 2009, p. 7

Sylvia Schedelbauer, Sea of Vapors, 2014, shown as part of Collected Works 2004–2018, Grazer Kunstverein, Spring 2019. Photography by kunst-dokumentation.com

Alice Butler is a Dublin-based film programmer, curator and co-director of aemi, a platform that supports and exhibits artist & experimental moving image work. Recent solo curatorial ventures include ‘The L-Shape’, an exhibition of moving image work by Jenny Brady & Sarah Browne at The Dock, Leitrim, ‘As We May Think’ at IFI, Dublin, and ‘New Spaces’ with VAI Northern Ireland. Butler has written for Sight and Sound, SET Magazine, Paper Visual Art, Enclave Review, VAN, EFS Publications, and CIRCA. She is a regular film reviewer for RTÉ Radio One’s Arena. She regularly presents screenings at Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane and she has lectured or participated in panels on the moving image in Ireland at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Project Arts Centre, PLASTIK Festival of Artists’ Moving Image, IFI, The Douglas Hyde Gallery, Galway Arts Centre, The Dock, University College Dublin and Dublin Institute of Technology.

Sylvia Schedelbauer, Remote Intimacy, 2007, shown as part of Collected Works 2004–2018, Grazer Kunstverein, Spring 2019. Photography by kunst-dokumentation.com

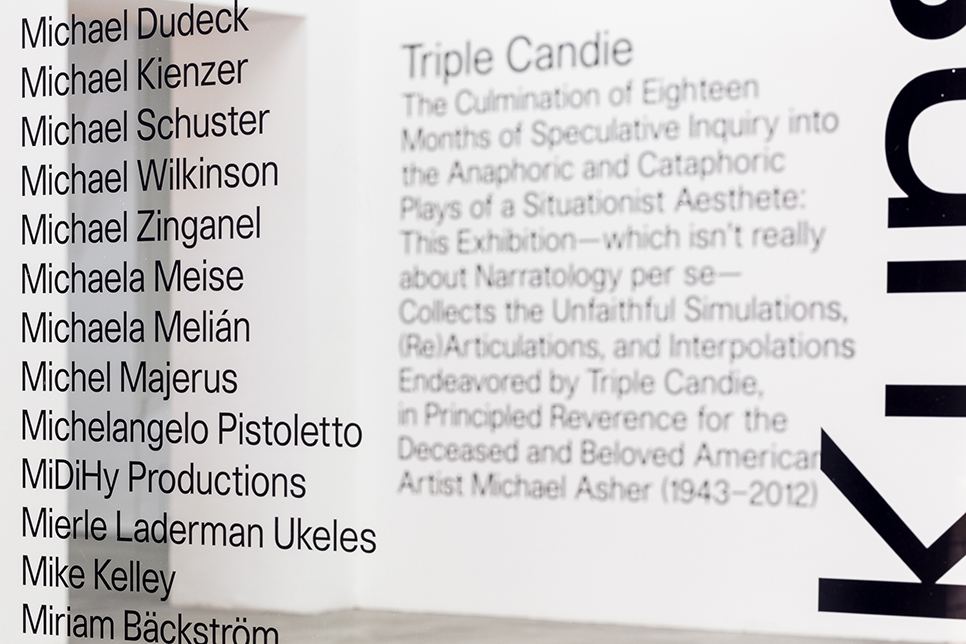

Triple Candie

The Culmination of Eighteen Months of Speculative Inquiry into the Anaphoric and Cataphoric Plays of a Situationist Aesthete: This Exhibition—which isn’t really about Narratology per se—Collects the Unfaithful Simulations, (Re)Articulations, and Interpolations Endeavored by Triple Candie, in Principled Reverence for the Deceased and Beloved American Artist Michael Asher (1943–2012)

Triple Candie, i. Untitled, shown as part of The Culmination of Eighteen Months…, Grazer Kunstverein, Spring 2019. Photography by kunst-dokumentation.com

Throughout 2018 and early 2019 Triple Candie (Shelly Bancroft and Peter Nesbett) undertook a multi-layered research project investigating the work and legacy of the legendary American conceptual artist Michael Asher. Asher is well known for creating temporary installations in museum and gallery environments, often foregrounding the various hidden systems and assumptions that make art viewing possible. Triple Candie researched his oeuvre in order to understand and embody his production methodology, and to apply it, in a new and moderately theatrical way, to the specific context of the Grazer Kunstverein.

Triple Candie, iv. Untitled, shown as part of The Culmination of Eighteen Months…, Grazer Kunstverein, Spring 2019. Photography by kunst-dokumentation.com

As part of the research project Triple Candie proposed multiple speculative installations, that were realised in a sequential seasonal rhythm throughout 2018. In practice, these installations were an attempt to resurrect the lost experiential potentialities of the work of an artist like Asher, asking ‘is it possible, through the speculative potential of arts practice, to reactivate expired gestures, in new or meaningful ways?’ Marking the culmination of this extensive research project, as part of the Spring Season we present a reprise of the first four installations, together with seven additional proposals that were previously unrealised. The exhibition will be documented with a forthcoming catalogue publication, contextualising the entire project.

Triple Candie, vi. Untitled, shown as part of The Culmination of Eighteen Months…, Grazer Kunstverein, Spring 2019. Photography by kunst-dokumentation.com

Triple Candie (Shelly Bancroft and Peter Nesbett) is a US-based, avant-garde curatorial production agency that collaborates with museums and contemporary art spaces on exhibitions about art but generally devoid of it. From 2001 to 2010, it had a gallery in Harlem. Since then, it has presented projects in Australia, Europe, and the United States at such venues as Chateau Shatto, Los Angeles, Deste Foundation, Athens, Gertrude Contemporary, Melbourne, Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, Project Arts Centre, Dublin, and Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, Salt Lake City. Surveys of Triple Candie’s work have appeared at FRAC Île-de-France/Le Plateau, Paris (2012), and Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, Massachusetts (2017).

Triple Candie, xi. Untitled, shown as part of The Culmination of Eighteen Months…, Grazer Kunstverein, Spring 2019. Photography by kunst-dokumentation.com

The project with Triple Candie was produced in collaboration with Phileas.

|

![]()

![]()